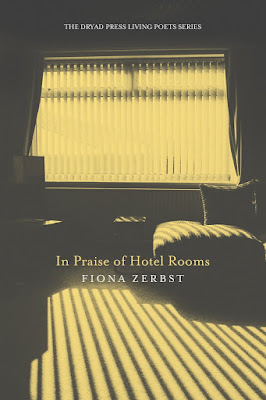

1. In Hotel Theory (2007) Wayne Koestenbaum reflects on the hotel room as a very specific space for writers. We think of Plath's movement in The Bell Jar from hotel room to asylum. Please explain your title: In praise of hotel rooms with reference to the programme verse:

In praise of hotel rooms

That hush behind curtains

you can’t describe later:

a hotel’s anonymous

shuffling of bodies, the cool, bland

surfaces lovely as rest homes:

fresh-paint complete.

I love oval tables,

blonde wood, deep-set lights;

bedspreads drawn back

like a fan’s tasteful opening. Scent

of corridors; acres

of sleep, like deep woods.

I harbour a vision

of animals grazing, at grass in the same

timid place, untroubled

by predators. These are the fields

of silence and pillows—

dream-sated, yielding to sheets.

Hotel rooms are peculiarly suited to writing poetry. One is suspended in time and space – one can rest without having to act, make decisions, or move around in the world. One can go within. In a sense, hotel rooms are little artificial pods of bliss. One can get lost in the “deep woods” of a hotel’s interior – one can be oneself without interruption (those ‘do not disturb’ signs are wonderful).

At the same time, each poem in the collection is a hotel room of sorts – a place where various artificial conditions make up a world.

2. There is a constant tension between the “homestead” and the foreign in your poetry. Comment.

As a poet, I find there is always a sense of longing tugging one away from the known to the unknown. Being a nomad, I have no sense of being ‘settled’ (I’ve lived in three provinces in the past ten years). I’ve been married to men from three different countries (Ukraine, Libya and Iraq), so there’s definitely a pull towards the ‘foreign’ in my life. I’ve never had the homemaking instinct, but I’m frequently nostalgic for my childhood, which is a home of sorts. I’m not sure that the kind of happy, settled home life many people have has ever been attainable (or indeed even desirable for me, in the final analysis). I’m too restless, and I need far too much space and silence.

3. You write ecological poetry, for instance on the extinction of the Javan tiger. How do you view so-called ecological poetry?

Ecological concerns are increasingly urgent in the face of climate emergency. Elizabeth Kolbert’s book The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History and The Photo Ark by Joel Sartore both touched a nerve, and I decided I wanted to figure out how to write about extinction, and what it might mean to be the last of one’s kind (a thylacine, a Javan tiger, etc.). It’s true that about 99% of species on earth have died out – that’s more than five billion – but I wanted to introduce a personal element to those statistics. Perhaps we can’t do much about losing these wondrous creatures; but we can write about it. I was also drawn to photographs in particular, like the photograph of what is ostensibly the very last thylacine. Susan Sontag has written: “The effectiveness of photography’s statement of loss depends on its steadily enlarging the familiar iconography of mystery, mortality, transience.”

4. Poetry is seen as the art of the present continuous, the iterative-durative. Please reflect on this with reference to the following poem:

Present continuous

Morning weeps. The dew is everywhere,

thick on leaf and petal. In the air,

tiny flies, newly hatched, are salad green

and sticky; wings attracting to their sheen

the morning’s handout of perpetual light,

its spit-wet, warm, intractable, slightest

radiance. Birds offer meaningless cries.

The night’s permitted language slowly dies

with brightness coming up. The day invades

the crevices of body, mind. These shades

of history’s continuous, afterthought past

are captured in photographs, hoping to last

beyond the hour and the purple of these

forever upturned morning glories.

Osip Mandelstam wrote: “Poetry is the plough that turns up time in such a way that the abyssal strata of time, its black earth, appear on the surface.” Some poems are, quite simply, about nothing more (or nothing less) than time – about what is always occurring (a bit like trauma). Poetry can heal the wounds of time, too – or simultaneously hurt and heal, as in Basho’s “

5. Why do you regards Raymond Carver as an important influence?

Three for Raymond Carver

I

Poems don’t matter that much

Poems don’t matter

that much. Language

hooks itself, a fish, to a stray line

caught on a rock, accidentally.

Look. Gutted because that line

was there in the first place,

taut, abandoned,

finished, messy, after the fact.

Poems. They only come

after you’ve tried living.

(...)

I discovered Carver’s poetry in my teens – actually, I heard the late Ron Smerczak read them at the Baxter Theatre, and they really came alive for me. He was a fly fisher and I attended to a fly fishing clinic when I lived in Pretoria. I became interested in fishing as a metaphor, and there’s obviously a long poetic tradition one can draw on in this regard – Carver, Seamus Heaney, Elizabeth Bishop. But I particularly like Carver’s overly blunt honesty, the frank way in which he faced his own shortcomings. I hope his work has influenced mine to some extent, though the influence may not be obvious.

6. In “Song for body” writing is an intimate bodily function. Julia Kristeva in Desire in language stresses this and the Afrikaans poet D.J. Opperman maintained: “You write a poem with your whole body.”

For me, writing is frequently somatic, and the story of the body must be told. Often, through language, one comes to discover what it is that the body knows. It’s an interesting process (and yes, it is one of desire).

7. In “Small” the loss of a parent is described. How do you see language? Belonging to the father or the mother?

I am not sure, but I think I am more “father sky” than “mother earth”. For me, language is about trying to return to the mother, I think (perhaps unsuccessfully).

8. “To write is to cry ...” in “The Bay” is a complex eulogy for Stephen Watson, a poetic mentor. The poem is a palinode on his poems. Comment.

I think the poem is about the difficulty of the poetic métier: “One keeps on writing. God knows why…” And the speaker’s mentor appears as a shade, perhaps warning about what is to come (“where waves pour into themselves”). It’s probably a fairly grim poem, on reflection.

9. “knuckling these pebbles of words ...” Do you think a poem should be concrete rather than abstract?

Yes, I strongly believe in the power of the concrete image.

10. You have travelled to many foreign shores. Please explain the following poem:

The Pantanal

~ Matto Grosso, Brazil

The lilac sky of the Pantanal

invites you to remember.

Deer and jaguar meet in your mind,

a painting by Rousseau.

Water lilies like dinner plates.

Flash of crimson macaw.

The pantaneiro will take you

to the blooming interior wall

to see beyond your dreams.

Nightjar over the dark lake

drinks in the cries unchanged

since before the human dumb-show.

For some strange reason, I wrote about the Pantanal precisely because I’d never been there. It dwelt in my imagination. I’ve visited every other place I’ve written about in the book.

When I worked as a travel editor, I was given a choice – visit Argentina, or visit Brazil. I chose Argentina, but there’s a part of me that stills longs for Brazil (of course). In this poem, I imagine an ‘inner Pantanal’, a mythical place of timelessness (perhaps the beginning of time itself). It’s a world pre-dating the human “dumb-show”, a world before ecological devastation (and perhaps, also, a world before language). In a sense, it belongs with my poems about extinction, but there’s also a mythological or psychological dimension to it.

11. Please share 2 of your favourite poems from your volume.

I find the images in “After Loss” very satisfying, for some reason. I also think “I Find No Solace” puts into words my philosophy about the world (such as it is).

After loss

I look for you in threaded strings

of rivers, or the blast of wind

through rocks; the sober cloud that forms

and darkens so that angels can’t

descend. That line of stones and pines

radiating from crumbling clouds

reminds me of the day we spent

close to each other’s panting breath

along the path. In losing you,

I’ve lost whole tracts of land—unfenced

inheritance—and gained the darkness

of this day that presses in

like rain that blots the horseshoe bay.

All I hold is words and shells,

like fragments of the lonely moon

whose craters cannot fill themselves.

I find no solace

There is no tinsel in the soul.

This is a desperate, lonely time.

Poor folk don’t end up in the tales

of Russian writers and the snow

is bleak on the window, barely festive.

Europe slips on ice, and slides

on history’s darkness. Hunched birds

are motionless on a frozen river.

Immigrants walk beneath a shred

of moon. I haven’t the time to see

how this will end, or if these stones

will speak from ruins. On the whole,

I find no solace, even in lines

of other writers, but what is true

is the poetry of Greek tragedians,

who loved beauty as much as we do.

© Joan Hambidge